Roadblocks facing Iran’s football privatization

Financial Tribune – TEHRAN, Iran’s football feeds on different industries, but it has yet to become an industry.

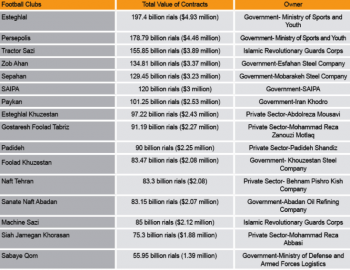

Tractor Sazi, SAIPA and Paykan football clubs subsist on automotive industry; Foolad, Sepahan, Zob Ahan and Gostaresh Foolad depend on the steel industry, while Naft Tehran and Naft Masjed Soleyman are patronized by the oil industry.

Acquiring detailed information on professional football business in Iran is a grueling task, as the officials of football clubs are not eager to provide data concerning their expenditures and revenues.

In the fiscal 2014-15, the Ministry of Sports and Youth announced, “Players of the Iranian Premier League receive as much as 15 trillion rials ($375 million) annually while the overall budget of the ministry is 4 trillion rials ($100 million).”

Back in July, the sports faction of the parliament announced Iran’s football has an annual turnover of 5 trillion rials ($125 million). “Finances associated with players’ income totaled 1.96 trillion rials ($49 million) in the 2015-16 Iranian Premier League. And this figure does not include undisclosed payments to the players,” the Persian weekly Seda reported.

All these speculations and guesswork about the value of Iran’s football market come, as many other countries release detailed information on the business of football as an expanding part of their economies.

Figures show the transfer market of 23 European football leagues plus their expenditures is worth around €20 billion, which equal Iran’s annual revenue from oil exports.

The privatization of two major state-owned football clubs, Persepolis and Esteghlal, seems like an intricate knot; the impossible task of untying it is passed over from one administration to another.

Lawmaker Ali Motahari, who is as vocal about football economy as he is concerned about politics, once said, “I’ve come to the conclusion that the government is not willing to hand over the clubs to the private sector and wants to keep this political, social capital. This is a feature of all governments so the parliament should intervene, create competition and end corruption.”

Another parliamentarian, Alireza Tabesh, said the government does not believe in privatization of these two football clubs and has no intention to do so.

“What remains of the Ministry of Sports and Youth without Persepolis and Esteghlal?” he asked.

“Any privatization deal should include the simultaneous transfer of ownership, shares and management. Expert meetings have been held and the two clubs were valued at around 3 trillion rials ($75 million) each at the base price.”

Persepolis had a private owner before the 1979 Islamic Revolution but the club was put under the control of the Physical Education Organization (now renamed the Sports and Youth Ministry) after the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

The other popular club Esteghlal, formerly named Taj, met the same fate. Since the PEO’s head (and, of course, the minister) are directly appointed by the president, the policies of the clubs were normally set by politicians. However, since more than a decade ago, when the Asian Football Confederation insisted on the privatization of professional football clubs, no state-owned clubs would be tolerated and deadlines have been set for reforms.

Following AFC’s warning, different scenarios have been considered for the two clubs, including listing them on Tehran Stock Exchange or Iran Fara Bourse. But the clubs’ accumulated debts and ambiguous financial situation prevented such scenarios from being realized.

According to Hassan Zamani, a board member of Esteghlal, the club’s debts are divided into two categories: One is the club’s debts to players, which amount to around 50 billion rials ($1.25 million) and the debts to Iran National Tax Administration, which hover around 300 billion rials ($7.5 million). Officials with Persepolis refused to comment on the club’s debt figures.

Mohsen Safaei Farahani, a veteran politician, and economic expert, who led the Iranian Football Federation from 1998 to 2002, believes the football business in Iran is the “full-length mirror” of the country’s economy. “You can spot the same financial indiscipline you see in the Iranian state-run economy in our state-run football clubs,” he said.