USA v Iran: The historic 2000 friendly match planned to bring countries together

BBC – LONDON, Paris, 11 July 1998. On the eve of the World Cup final, in a first-floor room in a building on the Champs-Elysees, an idea for a football friendly was hatched that would lead to death threats, an FBI decoy and the closure of American airspace.

That night, a media reception by US Soccer to promote the United States’ hosting of the 1999 Women’s World Cup was in full swing.

As the gentle currents of small talk circulated among suited attendees, two acquaintances were brought face to face.

Mehrdad Masoudi was an Iranian coming to the end of his time working as the Canadian Soccer Association’s communications director. Hank Steinbrecher was the General-Secretary of US Soccer. In football federations and confederations, very little happens without the signature of the ‘GS’.

Three weeks earlier, the two men had been in Lyon to watch Iran beat the USA 2-1. This group-stage encounter was one of the most politically charged matches in World Cup history because of the enmity between the nations.

Iran had been under US sanctions since 52 diplomats were taken hostage in the American embassy in Tehran in 1979, the year of the Islamic Revolution that toppled the pro-American Iranian monarch, the Shah.

But on the day of the match, in a US presidential address, Bill Clinton said he hoped it would be a step towards “ending the estrangement between our nations”.

Meanwhile, before kick-off, the American players were showered with gifts from their opponents.

Irrespective of the result, the match had been a diplomatic triumph and the occasion was still fresh in the minds of Masoudi and Steinbrecher when they met, albeit for contrasting reasons.

“I said, ‘Hank, how about repeating that?'” says Masoudi, who was well connected in Iranian football and wanted to help facilitate another match between the nations.

“Home and away games. Iran to come to the US next year, on the anniversary of this match, and you go to Iran the following year.”

Steinbrecher liked the idea. And he saw another opportunity too.

“The World Cup match with Iran was the worst defeat during my tenure,” he says.

“We hit the post three times. We didn’t suffer from bad soccer, we suffered from bad citizenship during that tournament, so I wanted to make it right. They kicked our ass, let’s go kick their ass.”

There was also the optimistic hope of somehow bringing Iran and America closer through sport, as so-called ping-pong diplomacy had brought the United States and China closer in the 1970s.

With a handshake between Masoudi and Steinbrecher, the ball was rolling. Now they had to defy the political forces arrayed against them, and somehow make it roll up a mountain.

“Fate brought the two teams together to play the France 98 match,” says Masoudi.

“This time, one side had to send an invitation to the other, who had to accept, and then both sides had to deal with their governments.”

The first, most sensitive and totally non-negotiable condition set by the Iranians was a waiver that would exempt the delegation from being fingerprinted and photographed on arrival in the United States.

“I have seen 80-year-old grandmothers going through that, I saw my own mother going through that,” says Masoudi.

“For someone who’s not used to it, it feels like they’re being treated like a criminal. I said to Hank, you have to talk to the State Department and US immigration to get an exemption.”

For Steinbrecher, this was the moment of realisation that an idea bounced around among canapes in Paris would have to negotiate an assault course of problems before coming to fruition in California.

“[It felt like] there was a crisis almost every hour,” he recalls. “It ranged from fingerprinting their players to the mullahs saying they’re not going to play the match because of alcohol advertising inside the stadium.

“There were many, many hurdles to jump through and luckily we were naive enough to think we were doing some good for mankind.”

Originally, the first match was set for the summer of 1999 in Washington DC.

But the symbolism of playing in the city of the White House was too significant for the Iranian government, which did not authorise the team to travel to the United States.

Instead, the game was rescheduled for January 2000, at the Pasadena Rose Bowl in Los Angeles, home to more than 500,000 Iranians who have nicknamed it Tehrangeles. It would be the final match in a three-game tour after friendlies against Ecuador and Mexico.

But two months out, in November 1999, the fingerprinting issue had become a seemingly insurmountable crisis. Thom Meredith, who was director of events for US Soccer, called Masoudi with the news that an exemption could not be secured.

Instead, the players would be fingerprinted and photographed in a private area of the airport in Chicago.

“I said ‘Thom, this is an absolute no-no,'” recalls Masoudi. “If I tell Iran they will just cancel the games right now. The contract was signed on this condition and, as an Iranian, I wouldn’t even ask this.

“It would have given the people who didn’t want this to happen the excuse to stop the team from travelling.”

The solution lay with the US Department of State – effectively America’s Foreign Office. It remained intractable, until a mysterious intervention saw the Iranians granted exemption, with just weeks to go.

“I don’t know what the chain of command was at that time, but my opinion is that this went very high up [in the US administration],” says Steinbrecher, who had been so long frustrated by the apparatchiks.

“We got it done, they got it done. But they did not see things through the same prism as our federation. There were not many people in the State Department tasked with international diplomacy through sport.”

However, if Steinbrecher and his colleagues thought they were through the worst, they had reckoned without the complex machinery of the Iranian government, in which the president is not the biggest component.

As the new millennium dawned, and just days before Iran were due to fly, the next political crisis was played out in Tehran.

Under pressure from his political masters to pull the trip, Iran’s reformist president, Mohammad Khatami, told the president of Iran’s Football Federation, Mohsen Safaei Farahani, to call it off.

“But Safaei had signed the contract and US Soccer had secured the waiver so Iran was contractually obliged to travel,” says Masoudi.

“The games were against quality opposition, and they were making over $200,000 for [playing] three games. Iran had never been paid this much to play friendlies.”

Safaei Farahani stood firm. It was decided: the tour would go ahead. At this point, Thom Meredith became a key figure.

“I wasn’t the guy who contacted different countries and asked for friendlies,” says Meredith. “I was the guy who was told, hey, we’re playing the Iranians, figure it out.”

Meredith travelled to Frankfurt to meet the Iranian team as it transited en route to the United States. It was there, in the transit lounge, that he came face to face with crises of his own.

“There was an Iranian player who met the team in Germany, where he played,” remembers Meredith.

“He was leaving his club after this tour and he showed me his apartment key. He said, I need to return my key so I get my deposit back.

“I’m like, ‘what the hell am I going to do?’ I wrote on a piece of paper to the head of delegation, ‘the United States Soccer Federation and Thomas P. Meredith take no responsibility for this player missing the flight.’

“He signed it, I signed it. It basically said, if he can’t get back to where we’re standing right now, in the transit zone, it ain’t Thom’s fault.”

The player did make it, but then, just before boarding the flight to Chicago, Meredith was told that nearly half the delegation had flights that had not been paid for.

“It was around 3am in Chicago. Who was I going to call? If I called somebody, what were they going to do? They’d probably hang up on me anyway,” says Meredith.

There was only one answer. He would have to foot the $13,000 bill himself (worth about £14,600 today), and keep the receipt somewhere very safe.

“My company credit card had a $5,000 limit. My personal credit card had a $30,000 limit. So I’m standing there, flipping the imaginary coin, thinking: ‘I’ve got to do this, but am I going to get my money back?'”

He did, as well as an upgrade to Business Class; reward for getting the relieved desk staff out of a serious hole.

For a few hours, the Iranian team were in the air, out of reach of destructive phone calls and on their way to America.

But when they landed at Chicago’s O’Hare airport, what everyone had prayed would not happen, happened.

“At immigration, we had a separate lane because they knew this was a special deal,” says Meredith.

“The agent started with the first guy, and they brought the ink pad out and said we need a fingerprint and we’re going to take your photo.

“Immediately, the head of the Iran delegation said: ‘We’re going home. We’re done. You lied.’

“I said, ‘Leave it with me, we’ve got this.'”

Like a conjurer, Meredith produced a letter from the head of the Chicago Immigration and Naturalisation Service, saying the Iranians were exempted.

So Iran’s footballers became only the second sporting delegation from the country, after a wrestling squad five years earlier, to set foot on American soil since the 1979 revolution.

The players’ liaison officer was Iranian-American referee, Esfandiar Baharmast. In 1972, he had joined a growing number of Iranian students who moved to the United States. Despite his academic expertise in chemical engineering, football was his passion.

After his playing ambitions were ended by a serious knee injury, he became a referee and officiated at the 1998 World Cup. By January 2000, he had become director of referees at US Soccer. But as an Iranian football fan, he was living the dream.

“I was with the players the entire time,” he says. “From the moment they arrived to the day they got on the plane to leave.

“We took them on tours, we went shopping with them, anything that needed to be done. We went on a tour of Universal Studios, the Golden Gate Bridge and Lombard street in San Fransisco.

“I just wanted to make sure that they enjoyed themselves, and I have to give a lot of credit to both federations.

“Hank Steinbrecher was a real man of the world. He saw the importance of this thing and did everything possible to make their stay comfortable.

“The games are won and lost, but for me it’s about the humanity and to see that game played with peace and friendship made me more proud than anything. The whole idea was that in 90 minutes of football, we can move the relationship between the two countries years ahead.”

Now that the Iranians were finally on US soil, a covert security operation swung into action.

“We had people who were undercover, watching and knowing where we were at any given moment, but not in an intrusive manner,” says Baharmast.

“If you didn’t know they were there, you wouldn’t have known who they were.”

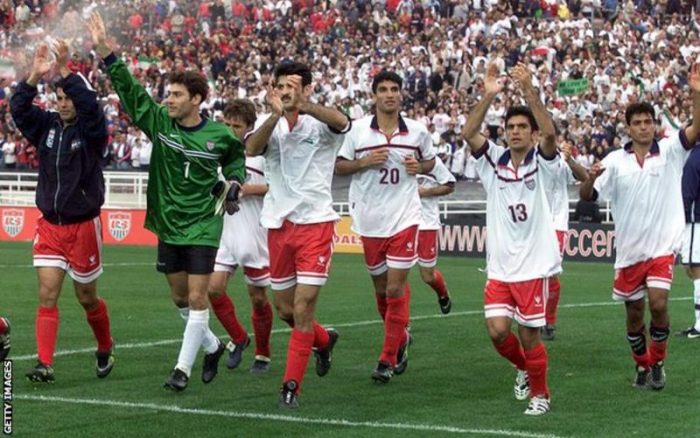

In their first two games, Iran beat Ecuador 2-1 and lost by the same score to Mexico, both times in front of raucous Iranian-American fans.

But as the match against the USA approached, joyous mingling turned into heightened awareness as danger slinked in the shadows.

The Iranians started receiving phone calls to their hotel rooms from a spurious Islamic group. Offers of bribes not to play and threats if they did were made.

“Two days before the match, the Iran coach Mansour Pourheidari said someone had called him and offered him $1m to pull out,” says Masoudi, who had taken leave from a new job in London to be with the team.

A call to Iranian football president Mohsen Safaei Farahani, claiming to be from the highest authority in Iran, threatened to down the delegation’s flight home if the match went ahead.

“I was there when he received this call,” says Masoudi. “He stood very firm and said: ‘The people you claim to represent know where I am. They have my phone number and they can call me directly themselves.'”

One theory, which was taken seriously, was that alcohol sponsorship at the match had offended the religious sensitivities of the threat-makers. The main match sponsor was due to be Anheuser-Busch, the company that brews Budweiser lager.

At a meeting on the eve of the match, the US Soccer Federation offered to switch to another sponsor.

“I said, well I know the guys at Anheuser-Busch, I’ll make good,” says then US Soccer General-Secretary, Hank Steinbrecher.

“I’ll give them more [advertising] signs another day. Nothing’s worth putting yourself at risk for, or this match.”

But Safaei Farahani adamantly rejected the offer.

“He said, as a soccer administrator, I know how difficult it is to bring sponsors onboard. The loss of an event is the loss of face for you with sponsors,” says Masoudi.

“I was translating and I had to hold back tears to finish the sentence.”

Steinbrecher recalls: “You want to talk about moral integrity? He showed me his colours. I have to tell you, he was a solid man.”

Nevertheless, steps were taken to protect the Iran players. Roads outside the team hotel were closed, and nobody was allowed to park near the hotel, apart from one vehicle, according to Masoudi.

“To make sure that the team wouldn’t be followed to the stadium, the FBI put a decoy bus outside the hotel, with ‘Iran’ branding,” he says. The actual team bus was kept out of sight in the hotel’s deserted underground car park.

The decoy, with fake footballers onboard, left first. As it began its journey, Iran’s national team was smuggled out through the kitchen and service lifts.

The Pasadena Rose Bowl had hosted two World Cup finals and the final of the 1984 Olympic football tournament. But it is doubtful any of those occasions had the singular atmosphere of this friendly.

In a move that now carries a chilling resonance given what was to come 18 months later on 9/11, the airspace above the stadium was closed in case someone was planning on flying a plane into it.

The tailgate parties that are a pre-match fixture of any American sporting event, when food and beer is served from cars, were all still there, but with a twist.

“Instead of steaks and burgers, it was Iranian kebabs,” says Masoudi.

“Outside the stadium it looked like a typical NFL occasion. But when you got closer and saw the people and smelled the food, it was clear that this was an American outing organised by Iranians.”

One of the 50,181 fans present was Saeed Mousavian, who had travelled to Los Angeles from Colorado.

“How many times do you get to watch your national team play? There was a feeling that this might not happen again,” he says.

“At that time I had an American girlfriend. She went with me and painted her face with the American and Iranian flags. A blonde girl with the Iranian flag. And I made her wear the Iranian shirt as well.

“After the game they asked one of the American players if he would like to go to Iran and play a friendly. He said, ‘We don’t need to because we were in Iran today.’

“It was just an awesome atmosphere. Everybody was happy. If the American team made a nice pass or tackle – even when they scored – we were cheering for it.

“I hated that they scored, but at the same time, it was a nice shot.”

It was Iran’s up-and-coming winger Mehdi Mahdavikia who struck first. Iran were then pegged back in the second half through midfielder Chris Armas’s equaliser. A 1-1 draw was the diplomatic result that couldn’t be exploited politically. But it didn’t help to thaw relations between Iran and the United States, as so many people had hoped it might, and tension remains between the nations today.

“We were naive,” says Steinbrecher. “We thought we were doing some really good things for both countries through our sport. But then again, if you’re not going to have a higher calling, you shouldn’t be involved.”

The return fixture that was mentioned as part of the original plan is still to be played. The USA were invited to a tournament called The Civilisations Cup in January 2001, they to represent the new world and Iran, Egypt and Greece the old. Their appearance fee was unaffordable for the Iranian Football Federation.

Still, for its architects, the friendly match that began the new millennium with hope for a better future was not all in vain.

“I have on my floor a prayer rug which was a gift from the [Iranian] delegation,” says Thom Meredith.

“It’s one of my prized possessions. In fact, if I had a fire in my house, I would probably grab that as one of the things to get out the door.

“I’m very proud of being a part of it, as a student of history, geopolitics and sport.”